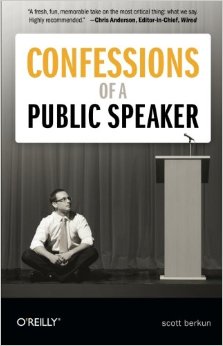

The notes I write down this time are about the book “Confession of a Public Speaker“, by Scott Berkun. Public speaking is one thing I do time to time, but I’ve been doing since lot of time. I had my first talk in 2005 and it was about “802.11b Insecurity“. Good book, with lot of real-life considerations and suggestions, many of which I’ve learned first-person during those years.

If I plan to do something in the presentation, I practice it. But I don’t practice to make perfect, and I don’t memorize. If I did either, I’d sound like a robot, or worse, like a person trying very hard to say things in an exact, specific, and entirely unnatural style, which people can spot a mile away. My intent is simply to know my material so well that I’m very comfortable with it. Confidence, not perfection, is the goal.

The slides are not the performance: you, the speaker, are the performance

It’s possible I’m not a better public speaker than anyone else – I’m just better at catching and fixing problems.

I admit that even with all my practice I may still do a bad job, make mistakes, or disappoint the crowd, but I can be certain the cause will not be that I was afraid of, or confused by, my own slides. An entire universe of fears and mistakes goes away simply by having confidence in your material.

Talking to some people in the audience before you start (if it suits you), so it’s no longer made up of strangers (friends are less likely to try to eat you)

Place matters to a speaker because it matters to the audience

You can play lecture drinking games with your friends, such as “ummmster,” where you do a shot of your favorite cocktail every time the speaker says “ummm.” With some speakers, you’ll be passed out in no time.

Most importantly, the density theory amplifies your energy. We’re social creatures. If five people – or even dogs, raccoons, or other social animals – get together, they start to behave in shared ways. They make decisions together, they move together, and most importantly, they become a kind of short-term community. The size of the room or the crowd becomes irrelevant as long as the people there are together in a tight pack, experiencing and sharing the same thing at the same time.

Ask the crowd if they’re too cold or too warm, and then, on the mike, ask the organizers to do something about it (even if they can’t, you look great by being the only speaker to give a care about how the audience is feeling).

Now I know I have to embody what I want the audience to be. If I want them to have fun, I have to have fun. If I want them to laugh, I have to laugh. But it has to be done in a way they can connect with, which is hard to do. A drunken toast at a wedding is often great fun for the toaster but miserable for everyone else. But great speakers are connection-makers, sharing an authentic part of themselves to create a singular, positive experience for the audience.

I’ve learned that by far the thing people seem angriest about is dishonesty. Show some integrity by speaking the truth on the very thing that angers them, or even acknowledging it in a heartfelt way, and you will score points. People with the courage to speak the truth into a microphone are exceptionally rare.

Request the names of three people to interview who are representative of the crowd you will speak to. See if your fears are real or imagined. Then, when giving your talk, make sure to mention, “Here are the three top complaints I heard from my research with Tyler, Marla, and Cornelius.” Including the audience in your talk will score you tons of points. Few people ever do this, and if the rest of the crowd disagrees with Tyler, Marla, or Cornelius, they can sort that out on their own after you leave.

The story is often told to suggest Lincoln’s brilliance – that he could just scribble one of the greatest speeches of all time in a few spare moments while riding on a train. It’s a story that inspires many to forgo preparing in favor of getting up on stage and winging it, as if that’s what great leaders and thinkers do. The fallacy of the legend is to assume that the only moments Lincoln spent thinking about the points he would make in the speech took place as he wrote them. That somehow he never thought about the horrors of the Civil War, the significance of human sacrifice, and the future of the United States except while he wrote down the words of the address on a random scrap of paper.

As you plan your talk, start with the goal of satisfying the things listed below. People come because they:

1) Want to learn something

2) Wish to be inspired

3) Hope to be entertained

4) Have a need they hope you will satisfy

5) Desire to meet other people interested in the subject

6) Seek a positive experience they can share with others

7) Are forced to be there by their bosses, parents, professors, or spouses

8) Have been handcuffed to their chairs and haven’t left the room for days.

A thoughtful speaker – a speaker without extraordinary eloquence or magic powers but who cares deeply about giving the audience something of use – can talk for 30 minutes, nail most of the first six, and end early, setting everyone free and having satisfied all of those in attendance (including those in the room for reasons seven and eight)

Audiences are very forgiving. They want the speaker to do well, so they will overlook many superficial problems. But if the speaker is not going to think carefully about his points, willfully disregards his own material, and gets lost as a result, how forgiving can the audience be? In most professional situations, such unpreparedness would be unacceptable.

Four things to prepare well for a presentation

1) Take a strong position in the title – All talks and presentations have a point of view, and you need to know what yours is.

2) Think carefully about your specific audience – If you don’t have time to study your subject, at least study your audience. It may turn out that as little as you know about a subject, you know more about it than your audience.

3) Make yours specific points as coincise as possible – Points are claims. Arguments are what you do to support your points. Every point should be compressed into a single, tight, interesting sentence. The arguments might be long, but no one should ever be confused as to what your point is while you are arguing it.

4) Know the likely counterarguments from an intelligent, expert audience – For example, if your presentation is about why people should eat more cheese, you should at a minimum know why the Anti-Cheese Foundation of America says people should eat less cheese.

People really want insight. They want an angle. A good speaker or teacher finds it for them.

If you think of a presentation as a kind of product, customer research makes sense. There’s no law stopping you from studying the kind of people you expect will listen to you and aiming your material at what they want to hear.

Good books like Garr Reynolds’s Presentation Zen (New Riders) and Nancy Duarte’s Slide:ology (O’Reilly) advocate such things. Try different ones to figure out which creative process works best for you.

In effect, by working hard on a clear, strong, well-reasoned outline, I’ve already built three versions of the talk: an elevator pitch (the title), a five-minute version (saying each point and a brief summary), and the full version (with slides, movies, and whatever else strengthens each point).

There are only a few things in the world that can silence a room full of people, and the beginning of a performance is one of them. And when I’m the speaker, I know that special moment is the only time I will have the entire audience’s full attention.

John Medina, molecular biologist and director of the Brain Center at Seattle Pacific University, believes 10 minutes is the maximum amount of time most people can pay attention to most things. In his bestselling book Brain Rules (Pear Press), Medina spends an entire chapter applying this theory to the challenges of teaching – the 10-minute rule is at the core of how he plans his lectures. He never spends more than 10 minutes on a single point, and he makes sure to structure the entire lecture around a sequence of points he knows the audience is interested in hearing. With enough study about the audience’s interests, and a 10-minute time limit, boredom can be kept at bay for an hour.

We want to catch and hold someone’s attention… Influence is a function of grabbing someone’s attention, connecting to what they already feel is important, and linking that feeling to whatever you want them to see, do, or feel. It is easier if you let your story land first, and then draw the circle of meaning/connection around it using what you see and hear in the responses of your listeners.

Know what the point is and what insight the audience will gain from what you are directing their attention to.

You do not have to be perfect, but you do need to play the part. In other words, be bigger than you are. Speak louder, take stronger positions, and behave more aggressively than you would in an ordinary conversation. These are the rules of performing.

Being on a computer means you instantly fall from being three-dimensional to two. They can still see you, but it’s a pixelated, washed-out, flat video version of you. The subtleties of your humor and the nuances of your points have a harder time coming through. To compensate, you have to project more energy. Doing so feels unnatural if you’re sitting alone in your cubicle, but your onscreen audience needs every extra bit of energy they can get from you to keep their attention from sliding away.

The simplest kind of tension to build and then release is problem and solution. If your talk consists of several problems important to the audience, and you promise to release the tension created by those problems by solving each one, you’ll score big. The audience will follow you through each sequence of tension and release. Other kinds of tension can be created by the premise of the talk. Your subject could be, “Why no one should go to school.” Your entire line of thinking creates a kind of tension, which you will release with each fact offered and point made.

“Any questions on what I just said?” This sounds threatening, like he’s daring you to challenge his authority, which many people won’t want to take on. Instead, make it positive and interactive. Say, “Is there anything you’d like me to clarify?”

Twenty seconds is more than enough time for a question; after 40 seconds, it’s a monologue and everyone in the audience hates him. But after a minute, people will be staring at you. You are allowing all of the energy to be sucked out of the room. They can’t do much about it, but they know you can.

Any time you are videotaped or recorded live without an audience, whether it’s for TV or the Web, it’s far worse being in an empty room than a tough room. This is why some shows have live audiences. They want to give their guests the many advantages of having the support and energy of real people.

People expect very little from most teachers. When listening to a lecture, most people are quite happy to just be entertained (being entertained is often more than people expect to get from any lecture). Learning, as a child or an adult, is often dreadfully boring, making laughter during the learning process a gift. Having likeable and interesting teachers is also rare, and quite pleasant, even though traditionally it’s seen as indirectly related to their ability to teach you something. Either way, a speaker can satisfy many audiences without providing much substance, provided he keeps them entertained and interested.

Credibility comes from the host. If the host says, “This is an expert on X,” people will believe it. People are willing to assume credibility based on how and by whom the speaker was introduced

Superficials count. Your appearance, manner, posture, and attitude matter. Every audience expects certain superficial things, and if you deliver them, the rest of your job is easier.

Enthusiasm matters. At the moment you open your mouth, you control how much energy you will give to your audience. Everything else can go wrong, but I always choose to be enthusiastic so no one can ever say I wasn’t trying hard.

This points out the real challenge in evaluating speakers. Whoever it is that invites someone to speak to an audience has to sort out:

* What they (the organizer) want from the speaker.

* What the audience wants from the speaker.

* What the speaker is capable of doing

If these three things are not lined up well, the survey will always have problems (e.g., Mussolini in London).

If you have two dedicated, reasonably intelligent people, one interested in teaching and the other wanting to learn, something great can happen. Think master and apprentice, mentor and protégé. For learning, small numbers win. The success of this one-on-one method is proven throughout history; many so-called prodigies were tutored by a parent or family friend (Einstein, Picasso, and Mozart all qualify). Yes, they had amazing, inherent talent, but they were still privately taught by people invested in their learning. Teaching is intimacy of the mind, and you can’t achieve that if you must work in large numbers.

I hear and I forget. I see and I remember. I do and I understand . It’s attributed to Confucius

The best research on learning suggests that the necessary shift is to switch from a teacher-centric to an environment-centric model. Most teachers focus on their lesson plans: what to include in their lectures, what textbooks or software to use, or where in the room they should stand. The teacher is the center of the universe. By contrast, the best teachers focus on the students’ needs. They strive to create an environment where all the pieces students need – emotional confidence, physical comfort, and intellectual curiosity – are present at the same time. The teacher has to get out of the way; instead of being the star, he is the facilitator who helps students gain experience. The teacher can achieve this through exercises, games, and challenges where he plays a supporting rather than a primary role.

My brother did the right thing from the first moment: he put me in the driver’s seat. Whatever happened next would have to happen through me, with his instruction. People never fall asleep if they are at the center of the experience.

In Ken Bain’s excellent book, What the Best College Teachers Do (Harvard University Press), he tells the story of Professor Donald Saari, a mathematician from the University of California, who uses the WGAD (“Who Gives A Damn?”) principle. On the first day of class, Professor Saari informs students that they can ask this question at any moment, and he will do his best to explain how whatever obscure thing he’s talking about connects to why they signed up for the course

Focusing on facts and knowledge makes it easy for the teacher to stay in control and at the center of the experience. In reality, the ability to do something only has a limited relationship to the quantity of knowledge you have.

Teaching is a compassionate act. It transforms the confusing into the clear, the bad into the good. When it’s done well, and the insights are experienced not just by the teacher but by the students as well, everyone should feel good about what’s happened. It’s amazing how rare it is in many systems for the experience of learning to be a pleasurable thing.

Sometimes people at my talks know much of what I know. In these cases, my value is to remind them of an old idea or put it into a new context.

Paying attention makes things funny . If I have any secret to being entertaining, it’s that I studied improv theater. There I learned how to see and how to listen. Humor and insight come from paying attention, not from special talents. After I studied improv, my speaking skills improved dramatically and my attitude about life changed. I can’t recommend taking an improv theater class strongly enough.

To love ideas is to love making connections. This is why people who bludgeon others with knowledge, intimidate with facts, distort intended meanings, and cherry-pick their examples are so easy to hate. They work against progress. “Only connect” is great advice. If you don’t know what you’re connecting through your words, you’re more selfish than you realize.

Making connections with people starts by either getting them interested in your ideas or showing how interested you are in theirs. Both happen faster the more honest everyone is.

Nothing kills your power over a room as much as a lack of silence. Silence establishes a baseline of energy in the room. Sometimes when a room is silent, people pay more attention than when you are speaking (a fact many don’t know since they work so hard to prevent any silence when speaking). If you constantly fill the air with sounds, the audience members’ ears and minds never get a break. If what you are saying is interesting or persuasive, they will need some moments between your sentences and your points to digest.

They (audience) should not be doing the hard work – you should. You are up there to share, persuade, or teach, and that means you have to drop the defenses, think clearly, and be at the level your audience wants.